Performing the Concert for Piano and Orchestra

Preparing parts for the Concert for Piano and Orchestra

Performing the Concert for Piano and Orchestra

Introduction

Having prepared and rehearsed a solo part, then performing it alongside one or more other players also playing their prepared solo, transforms the piece from a sequence of isolated sounds, albeit rather unusual sounds, separated by silences, into an adventure of sonic collisions, surprises, silences (still) and revelations.

Timing and duration

Cage’s instructions state: ‘Though there are 16 pages [or 12 for instruments other than strings], any amount of them may be played (including none).’ Instrumentalists have variously taken this to mean any number of pages may be played, or any number of sounds from a page may be played. Either way, the player is given a degree of freedom to choose how to construct a part for performance. Often, players choose to rearrange their pages and play in a different order from that presented in the part. One would think that this would make no difference to the whole, since what appears on the page is, in some ways, randomly selected. But one of the elements which is randomly determined is the possibility of changing the tuning of individual strings or changing the instrument being used from, say, a flute to a piccolo. Although each page is, in theory, just like any other, these changes run sequentially and rearranging the order of pages can lead to confusion. As such, when playing only part of a part, it is often a good idea to retain page sequence and continuity, playing, say pages 3 to 6 inclusive rather than 3, 6, 8, and 11.

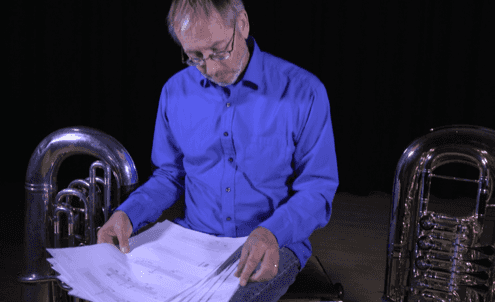

Constructing a part is a sufficiently flexible process to allow players to make a sequence that works for them, though it may be that players wish to agree some common principles for making a part. But ultimately as long as a total duration is agreed then individual players can make those decisions for themselves. Usually players inscribe timings in some way on their scores. For example, a player might allocate 30 seconds to each system, thus allocating a duration of 2′30″ per page. If a total duration of 15 minutes is required then the player would play six pages. Remember also that all players, other than the strings, have the option of adding additional silences. Alternatively, the player could assign a much more complex set of timings, such that one system might last 10 seconds, another might last 30 seconds and still another might last two minutes, or 1′42″ (or indeed 4′33″). Different timings such as these might reflect, if the player so chooses, the density of the system, such that especially dense lines are assigned longer durations. Or timings might be allocated using a random procedure. Alternatively, players may choose not to add timings to systems at all, and simply ensure that they move through their parts freely until the agreed finish time. Archival sources and correspondence suggest that in early performances string players assigned (or were assigned) 15 seconds per system, and brass and wind players 20 seconds per system, meaning that all pages could be played in a total duration of 20 minutes. This is fast, and undoubtedly would have forced players to prioritise some events or ways of playing over others in those systems which contain many sounds to be played.

The Apartment House musicians took all sorts of different approaches to timing and duration in the Concert. Some players worked at the level of a page or system, assigning a duration accordingly. Clarinettist Vicky Wright set herself a minimum time limit for each page, depending on how busy the page was. Working somewhat contradictorily, violinist Aisha Orazbayeva allocated a shorter duration to the busiest pages. Cellist Anton Lukoszevieze was less concerned with timings in terms of seconds or minutes, and instead focused on the physical position of the conductor’s arms. Working at the level of a line rather than a page, he used chance procedures to decide how to divide up his pages, and how many revolutions each line or page would take. He also inserted silence at the beginning of his performance.

If a conductor is not being used then a sequence of pages and timings may be compiled that total an agreed duration with players following a stopwatch or some other means of measuring time. If a conductor is employed then it is most important for players to mark in timings that are practical to follow in relation to the conductor’s arm rotations. A simple approach would be to assign a system or two systems or some such number to a minute of conductor time, that is to a single rotation of the arms. And of course players need to be ready to adapt their speed of moving through a system or a page in response to the changing speeds of the conductor’s arms. This may require shortening durations of sounds, or even missing sounds out, if a sudden increase in speed occurs, or holding sounds for considerably longer than planned when the speed slows dramatically, or simply enjoying the wait.

The performance space

The Concert is often performed with musicians separated in the space in some way, even sometimes with musicians widely dispersed in and around the performance space. Cage doesn’t specify this in the instructions, but the very separate nature of the solos encourages such an approach. If this approach is taken, then one has to consider where to place the conductor. Cage was certainly on his way to thinking about such matters at the time of composing the Concert, which is contemporary with a number of deliberately theatrical works and works which encourage consideration of the space in which sounds and actions are made (such as Theatre Piece (1960) or Music Walk (1958)). In an interview from 1965 with Michael Kirby and Richard Schechner, Cage said:

When you have the proscenium stage and the audience arranged in such a way that they all look in the same direction – even though those on the extreme right or left are said to be in ‘bad seats’ and those in the center are in ‘good seats’ – the assumption is that people will see it if they all look in one direction. But our experience nowadays is not so focused at one point. We live in, and are more and more aware of living in, the space around us. […] More pertinent to our daily experience is a theatre in which we ourselves are in the round […] in which the activity takes place around us. (Schechner & Kirby, 1965, 51–52)

The disorienting impact of such a layout on the listener, both visually and aurally, is captured in an anonymous review of the Austrian premiere of the Concert:

There was practically no-one on the stage. One looked for musicians there in vain. They were seated partly in the gallery, partly in the stalls, scattered wide across the whole hall Around them, the audience no longer knew in which direction it should orient its ears. ([unsigned author], 1959)

Experiencing the Concert in Performance

In a performance of the Concert, then, players adhere to their own parts, and play what needs to be played in relation to the passage of time, regardless of the players around them. Or so the conventional Cageian performance practice goes, not least propagated by Cage himself. Such an approach is suggested in a letter he wrote to the composer Charles Boone about performing Variations III (1962–63):

Only a musician who is willing to undertake the [p]erformance in a disciplined way (i.e. a way not constrained by his likes and dislikes) should do so. Let his rehearsal be in solitude, not together with any of the other musicians. The music may be performed theatrically (i.e. include actions to be seen, or to be noticed) but it need not be. No one is to constrain or be constrained by another. (John Cage to Charles Boone, 21 March 1968 (source: John Cage Collection))

Writing from a performer’s perspective, a similar view is articulated about the Concert itself by Petr Kotik, the conductor and Director of the S.E.M. Ensemble, who has performed Cage’s music widely:

The Concert for Piano and Orchestra […] require[s] a perfect balance between discipline and free choice. The choices that the notation allows each musician should never be made according to personal wishes, but instead must always employ objective strategies. […] [E]ach musician is ‘free’ to choose the speed with which to read his individual staff of the score. However, these choices must not be made merely according to the performer’s preferences. For example, the musician cannot choose to stay longer with the sections he likes, or skip those he dislikes. […] The purpose of such an approach is to remove value judgments from the decision-making process. One should never put one’s own ego between the music and the performance! (Kotik, 1992)

However, experience of performing the Concert suggests that ignoring the sounds being projected in and bounced around the performing space is very difficult. As violist Reiad Chibah commented during interview:

The sense of space, and being evenly spread out with other performers, and each one providing these points of interest, it’s not like anything else that I’ve done. There’s a sort of transparency with the distance and also the amount of silence, and the amount of time a lot of the players aren’t playing, it’s really satisfying. You feel like every action or moment, you can certainly hear it, which is not always the case if you’re a viola player. […] In that sense, everything matters. [...] So it’s really satisfying, from that point of view.

The sounds made by other members of the ensemble, at times humorous, at times shocking and at other times delicate and beautiful, inevitably impact in some way upon the performance energy. It is difficult not to respond in some way, consciously or otherwise, even if that response is not to play, or to play a sound for a little longer, or a little louder, or a little more exaggeratedly. Trumpeter Jonathan Impett reflected on this situation during interview:

You find yourself playing with the urge to play with other people. […] And I think that challenges your listening, it challenges your musicianship, it challenges your experience and your understanding of what it is to play with other people.

The restrictions made upon the players by the notation are considerable, but not rigid, and the notation is such that performers may or may not choose to change their sound in the moment of performance. The musicians responded to these circumstances in different ways. Flautist Nancy Ruffer observed that she sometimes felt the urge to adapt her playing in response to the actions of the conductor and to the other musicians:

I think what I found the most difficult was when the conductor’s hand actually stopped moving, and I felt I wanted to continue a sound or come to the next sound quicker, and I had to just stop everything. And other times I felt there was a lot of noise from other instruments going on, but I also had quite a dense collection of sounds, and I wondered how I could be heard through the other instruments, and I would find myself waiting for pauses where I could make a little sound, especially if they were soft.

By contrast, Lukoszevieze commented that, since performing the piece could be such a disorientating experience,

I’m not listening and reacting to anybody else—the piano or anything—I’m just doing the job I have to do. And I try to be very, very strict about that, and very concentrated about it. And it’s actually quite exhausting just sitting there waiting to play. Because you don’t want to be distracted, and you really just have to prepare yourself in your mind about what you have to do, that’s coming up.

Even if one adheres very strictly to the space-time notation, aspects of duration and dynamic at the very least are left open. There is undoubtedly a freedom within the notation which is different from the freedoms associated by early performances, in which musicians played in ways definitely not suggested by the notation, to supposedly humorous effect. As Cage once said, reflecting on these early performances, ‘I must find a way to let people be free without their becoming foolish.’ (Cage, 1961, 118). There is both freedom and discipline in performing the Concert for Piano and Orchestra, and a strong performance will reflect both these elements, with individual players responding to the challenges of the piece with both curiosity and discipline. This leads to what Cage called ‘the practicality of anarchy’, or ‘[a] group of people acting without anyone telling all of them what to do’ (Cage 1974, 81).

Bibliography

John Cage, ‘Indeterminacy’, tr. Hans G. Helms, Die Reihe, vol. 5 (1961 [1959]), 115–120

John Cage, ‘Reflections of a Progressive Composer on a Damaged Society’, tr. Hans G. Helms, October, vol. 82 (Fall 1997 [1974]), 77–93

Petr Kotik, liner notes, John Cage: Concert for Piano and Orchestra/Atlas Eclipticalis (Wergo, WER 6216-2, 1993)

Richard Schechner and Michael Kirby, ‘Interview with John Cage’, Tulane Drama Review, vol. X, no. 2 (Winter, 1965), 49–72

[unsigned author], ‘Tumulte im Mozart-Saal des Konzerthauses: Musiker saßen im Publikum, Reindl, Wecker und Türen spielten mit—Ein Konzert der “reihe” führte zu Demonstrationen—Klavierkonzert von Cage: mehr Sensation als Musik’, Neues Österreich, 21 November 1959