Solo for Piano

Philip Thomas: Performing the Solo for Piano

Introduction

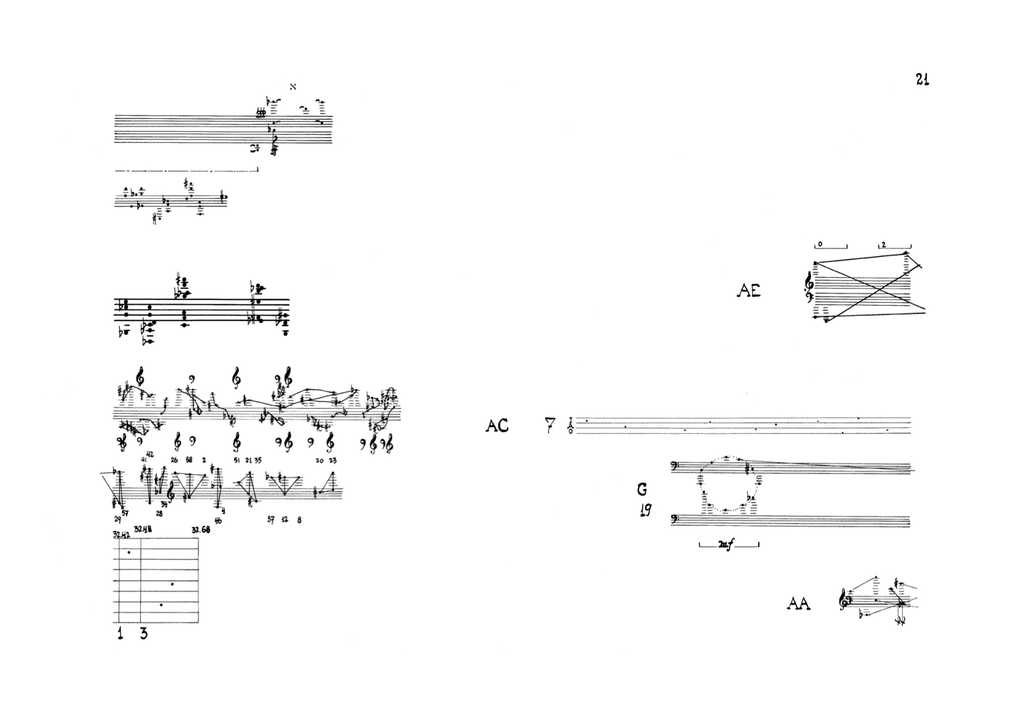

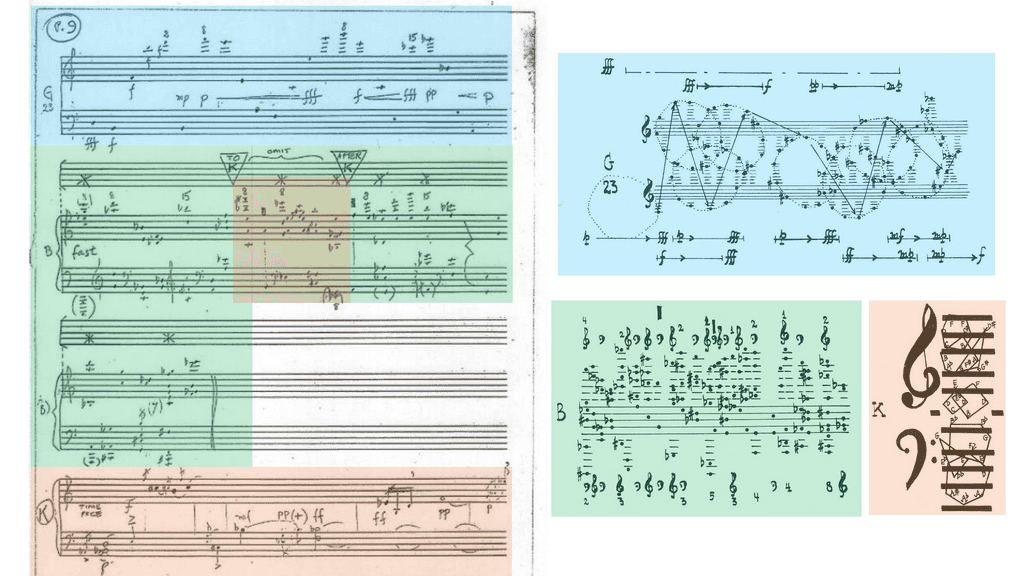

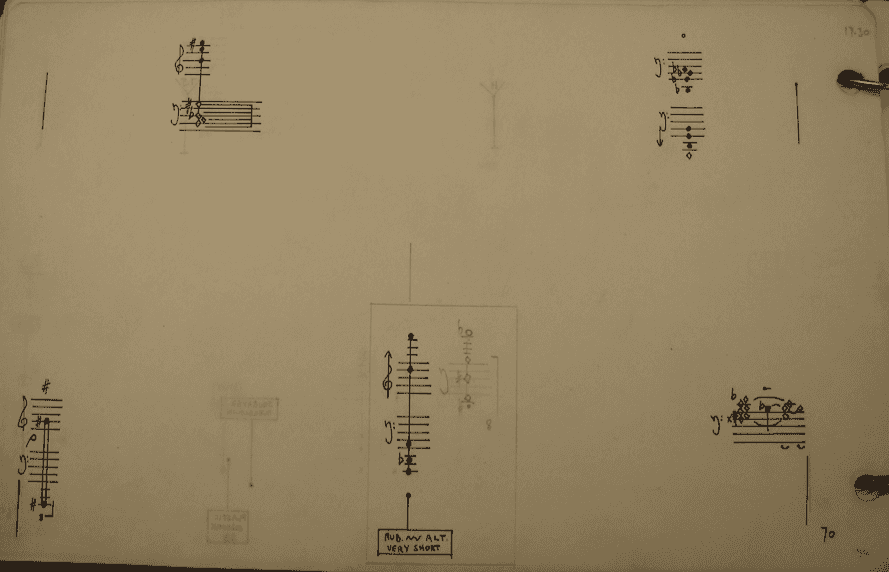

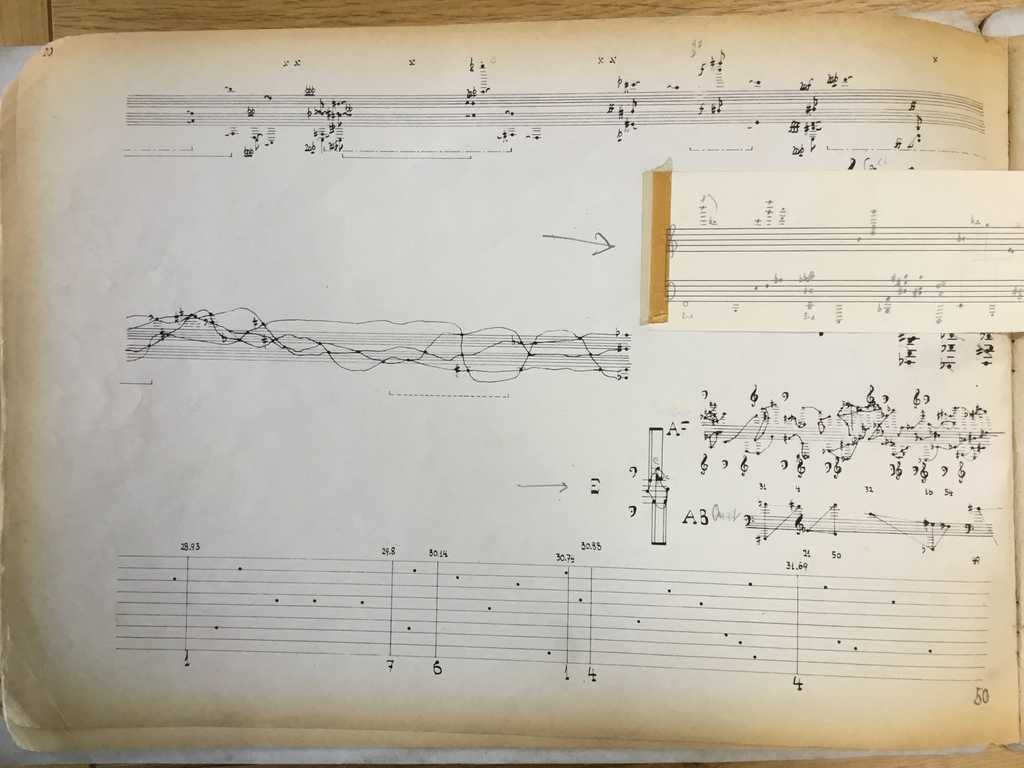

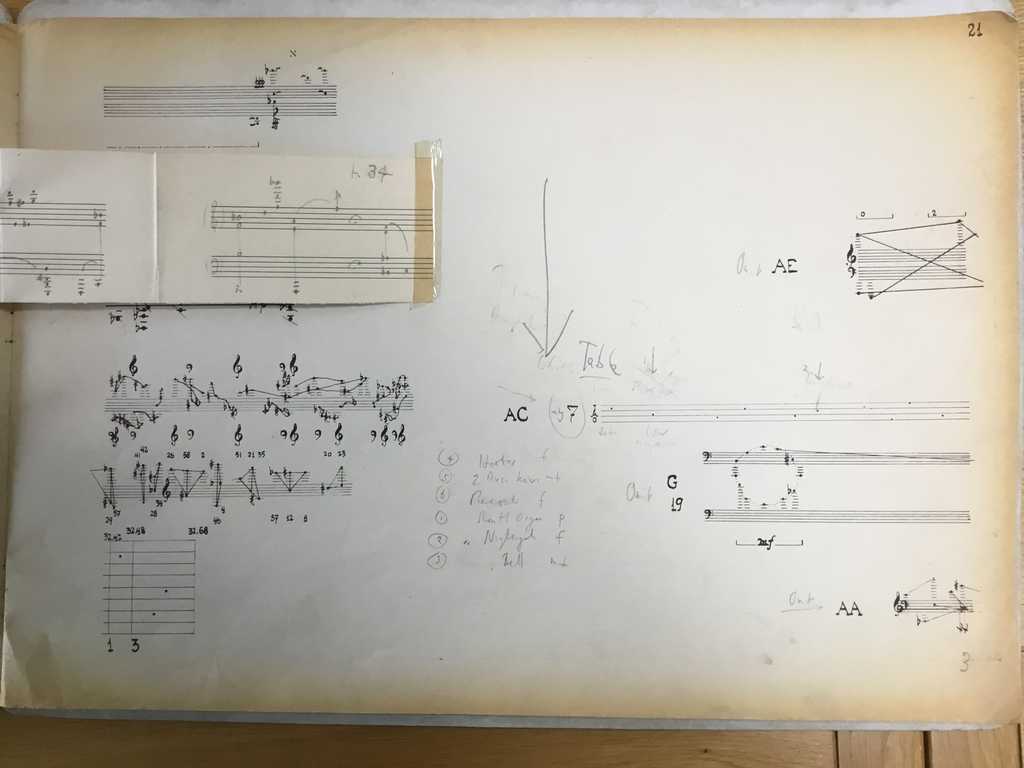

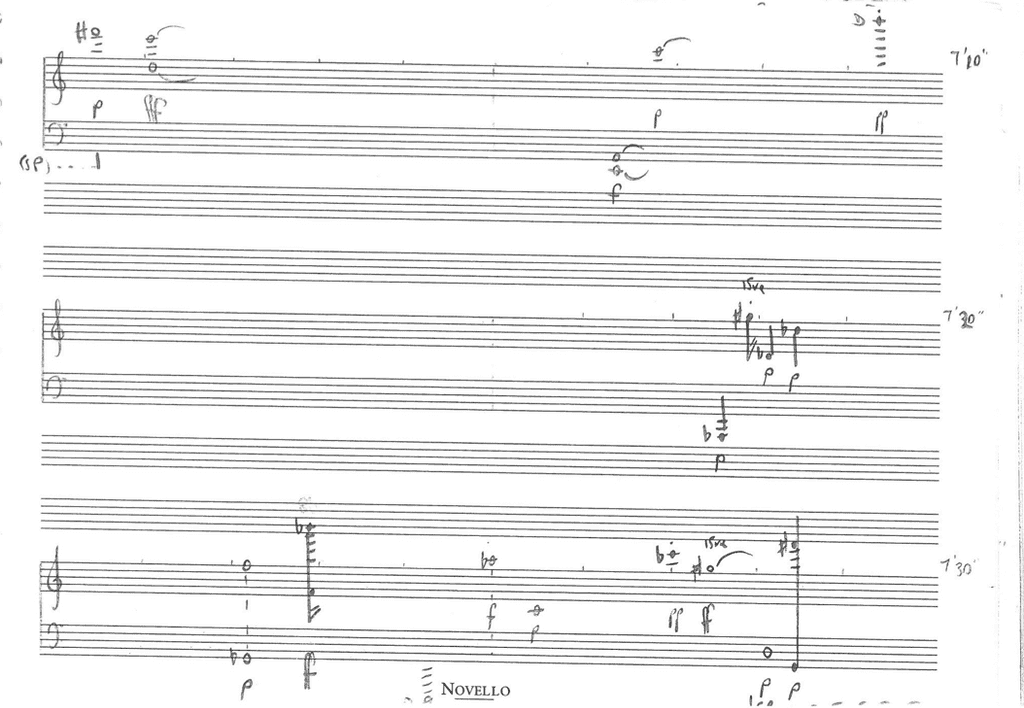

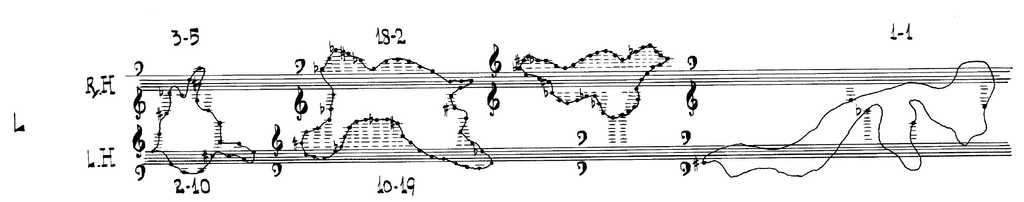

When the artist Elaine de Kooning (pictured here third from right, standing just in front of John Cage, at Black Mountain College for a cast portrait for the production of The Ruse of Medusa) commissioned Cage in 1957 ‘to write a tiny little work for me’ (Elaine de Kooning to John Cage, ca. 1957 (source: John Cage Collection)) she could hardly have imagined receiving a score of the magnitude, abundance and diversity of the Solo for Piano: 63 pages of extraordinary graphic variety, featuring a total of 146 notations of 84 types, ranging from those which have the appearance of conventional music notation to others which are highly abstract and diagrammatic in character. One could easily imagine someone encountering the score for the first time today sharing De Kooning’s reaction to it: ‘unbelievably beautiful’, but also admitting to being ‘overwhelmed’ and even ‘terrified’ by it.

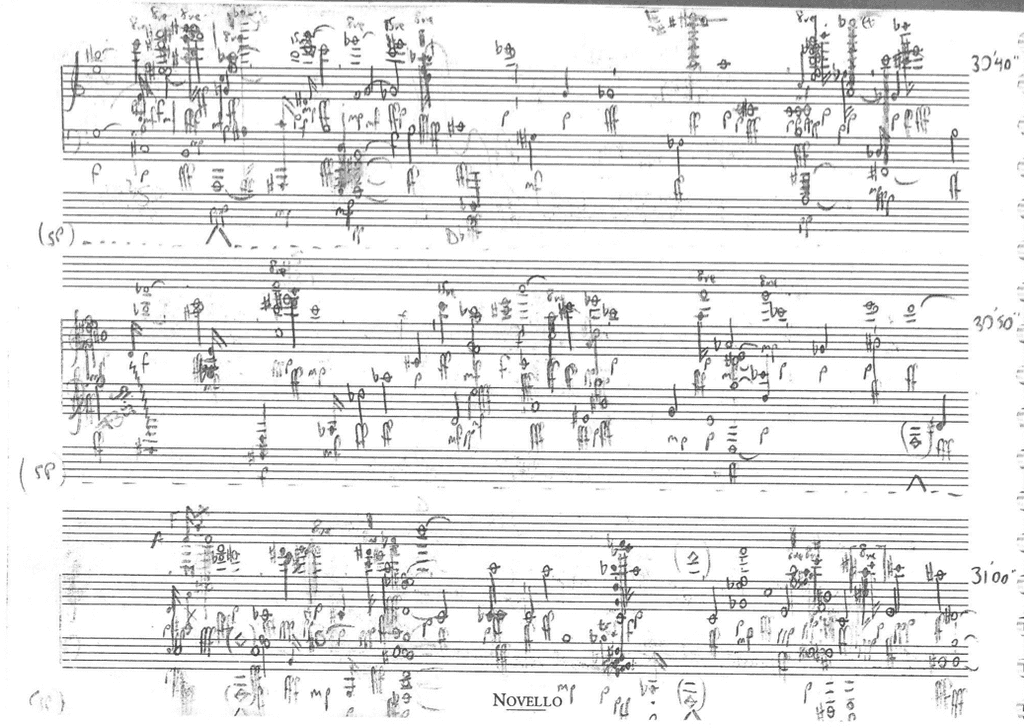

The notations are arranged across the pages in striking ways: short, large, narrow, long, thin, and thick notations are distributed such that a notation may take up the smallest window of a page or may extend across a number of pages. A single page may consist of as many as ten notations arranged vertically, horizontally, or unpredictably, or as few as one or even zero notations (there are three entirely empty pages). The score is a visual feast—indeed, pages have frequently been exhibited as objects to be looked at—but as music to be played the rewards are more hard fought for.

Preparing a performance

The main challenges for the pianist might be summarised as 1) what and when to play (which notations, in which order, and for how long); and 2) how to play (how to translate the graphics into sounds to be played at the piano), though not necessarily in that order. Regarding the first of these Cage stipulates very little: in the instructions he writes: ‘Each page is one system for a single pianist’ and ‘[t]he whole is to be taken as a body of material presentable at any point between minimum (nothing played) and maximum (everything played), both horizontally and vertically.’ Added to this is his programme note which states that ‘[t]he pianist is free to play any elements of his choice, wholly or in part and in any sequence.’

Taking Cage at his word, one could say that a performance of the Solo for Piano could consist of silence (either the decision not to play anything or the intentional ‘playing’ of one of the empty pages) or could contain everything from across the 63 pages, though even then one might struggle to declare such a performance as ‘complete’ given that a number of the notations require the pianist to select from the given material and not to play everything available. (As far as is known, no-one has performed the Solo for Piano in such a comprehensive state, but it is possible to hear such a version, performed by Philip Thomas, in a studio recording which combines separate recordings of each notation and arranges them to map onto their sequence and combination in the score). As pianist John Snijders said in interview, ‘it’s, as far as I know, the only piano concerto in which the piano need not play at all.’

Selecting which notations to play is a choice left entirely open: pianists may delve into this compendium of music notations at will. Yet the pianist might be mindful of the instruction that each page is one system, an instruction which, taking into account the irregular vertical alignments of notations and the fact that many notations run across multiple pages, is not entirely straightforward. Joseph Kubera, a pianist very familiar with the Solo for Piano having performed it widely, adopts an approach whereby two or more notations from the same page might be combined or interpolated in some way, but only as a general rule, acknowledging that the various complexities of timing and means of interpreting the graphics mean that literal left-to-right superimpositions are frequently not possible.

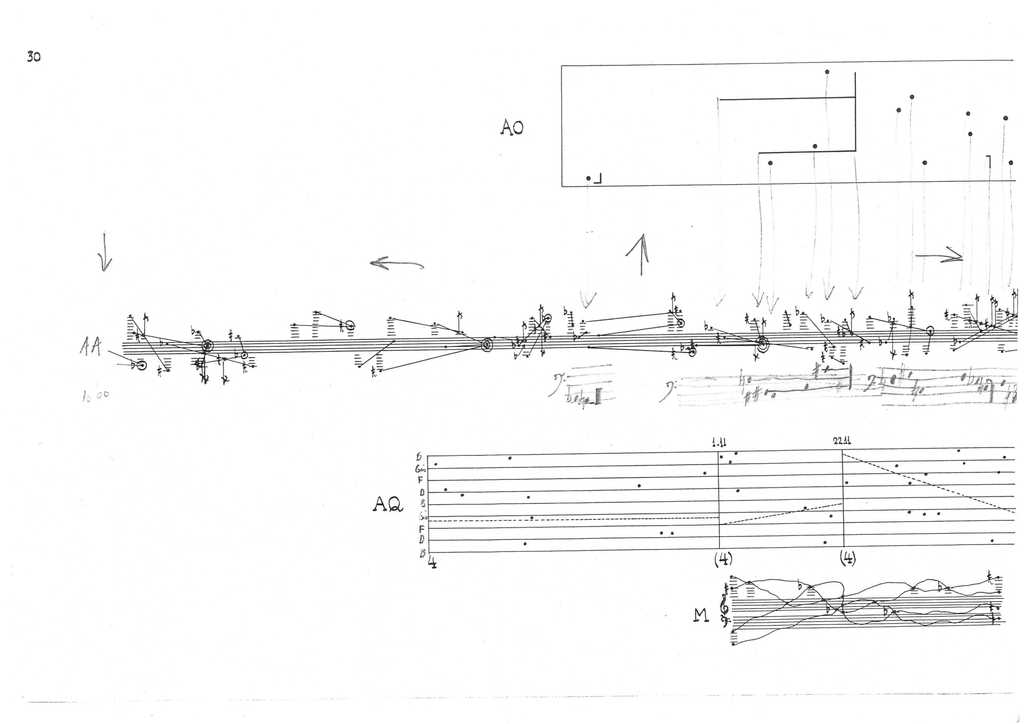

Thomas Schultz’s recent recording of the Solo (John Cage: The Works for Piano 10, 2018) also presents notations singly or grouped, and Snijders’s realisation of AA and AO on page 30 can be seen below.

Philip Thomas’s realisation has combined all notations on the pages selected according to their size and position on the page, and the version available on the Concert Player app combines all notations on a page by superimposing separate recordings of individual notations.

David Tudor’s extraordinary and idiosyncratic second realisation of the Solo for Piano (heard on Indeterminacy: New Aspect of Form in Instrumental and Electronic Music, 1959) combined notations by stretching each notation until it had a duration of 90 minutes and effectively superimposed up to 30 of them.

By contrast, one might choose to play any sequence of notations one after another, presenting each one as its own ‘piece’, as in a traditional Suite. Some recent solo recordings of the Solo by Stefan Schleiermacher (John Cage – Early Piano Works, 1993; John Cage – Complete Piano Music Vol. 4., 1999) and Sabine Liebner (John Cage: Solo for Piano, 2013) adopt this approach, while Giancarlo Cardini’s performance, combined with Francesca Della Monica’s performance of Cage’s Solo for Voice 2 (1960) (Cage a Firenze, 1993), consists of notation B (pp. 34–35) only (which is a version of Cage’s Winter Music (1957), a piece that Cardini has also performed). Similarly, though more perversely, Stephen Drury recalls a performance with ensemble, and a singer performing Aria (1958), in which he chose just to perform notation I from page 29, consisting of 57 iterations of the same note, a muted D3, which he stretched out over the whole ten-minute performance. Pianist Fabrizio Ottaviucci (John Cage: Dream, 2009) recalls two very different performance experiences: in the performance for the WERGO recording of the Concert ‘I had chosen only one page, the duration was about 15 minutes and there was interaction between the will of the director and my choices; [...] in the second [performance] the duration was about 60 minutes, I selected a large number of pages (I think a dozen), I worked completely by myself.’

As will be seen below, many of the notations require some kind of transcription, although some might plausibly be read from Cage’s score. Performers interviewed for this research project have varied in their methods and approaches. Some have made annotations on their copy of the score and have played from this, placing it directly on the piano stand (or elsewhere, to allow for inside piano techniques, for example, Snijders as seen here); others have taken a combined approach, mixing some pages of the published score from which notations can be more easily read with other manuscript pages featuring notations they have realised in their own hand; while others have made an entirely new (secondary) score which maps out all of the notations used for a given performance. The latter option does not necessarily ‘fix’ the piece: the pianist might make fresh realisations for each performance, or, as Kubera does, ‘collect’ realisations, making new ones and re-using old ones for each performance. However, some pianists interviewed were keen to ensure that further elements of spontaneity were preserved in their performances, and intentionally left themselves free to interpret some aspects in the moment of performance.

For the performance with Apartment House featured here Thomas chose to make a ‘fixed’ version, notating pitches, noises, timings, even dynamics, for the most part. Durations of sounds were mostly left free, as were some noise elements. The following structure was applied to generate a realisation aimed at 45 minutes (though which, for a number of notational reasons, turned out to be 53 minutes), with random selections made using both a random number generator and Andrew Culver’s I Ching program ic, which allows for random divisions like those used by Cage to be integrated within the calculations:

- Pages were selected randomly

- Pages were determined by chance to be read either sequentially (one page after another) or as lasting the total duration of the piece (45 minutes) with a bias of 1:6 in favour of the former

- If the former, page durations of between 2–5 minutes in 10-second increments (19 possibilities) were determined by chance

- Pages were read in their entirety, as a ‘system’, from left to right only

- If a notation starts earlier or continues later, that notation only begins/ends earlier/later proportionately in time to the duration of the page (i.e., in a 45-minute reading of a page, the whole page would begin/end earlier/later than the total 45 minutes)

- Questions relating to dynamics, attack, etc. pertinent to any notation were determined in relation to that specific notation

As a result, just 14 pages were selected (3, 5, 11, 19, 25, 27, 28, 29, 32, 37, 45, 52, 54, and 61—though not in that order), meaning a total of 49 notations were realised, although some of these were repeated (such as those which run across pages 27, 28, and 29).

Having completed the process of transcribing these notations such that they fitted within the time structure described above, Cage’s score was then replaced by the secondary score notated in Thomas’s hand, which was used for practising and the performance. In this sense, the Solo for Piano requires practising just like any other: although some notations could be sight-read or improvised within the limits set by the instructions, many probably can not (though the openness of duration means that possibilities for performing very slowly are permitted). The majority of the notations are fixed in some way, or allow for limited choice (such as clefs), and for much of the time there are right notes (or sets of right notes) and wrong notes. At the same time, it should be noted that some combinations of page and duration proved to be especially complex and challenging, to which Thomas’s response was to recall Cage’s own performance approach to narrating his 45′ for a Speaker (1954): ‘Not all the text can be read comfortably even at this speed, but one can still try.’ (Cage, 1968, 146)

Whichever method is adopted for making a realisation, some kind of decision is needed as to how to proceed from one notation to another. This might be fully planned out in advance, if a secondary score is used, or it might be more intuitive, even improvisatory, making decisions in the moment of performance itself. Marianne Schroeder recalls that in her performance with the Barton Workshop (The Barton Workshop Plays John Cage, 1992) she had a number of realisations ready to hand, spread out over the piano, and moved from one to the next spontaneously in performance. If performing with a conductor, some discussion is required as to how and when to begin and end, whether to follow the clock or respond to the conductor’s closing gestures. Conventionally, the pianist performs independently of the conductor’s movements, which govern the speeds at which the other instrumentalists move through their parts, but the Solo for Piano instructions might be read such that the pianist could also follow the conductor’s time shifting, a reading that among pianists interviewed for this project only Snijders has adopted in his performances with the Ives Ensemble.

All of the above—and much more could be mentioned as to the choices pianists make, consciously or not—points to the fact that the pianist’s role goes beyond what is usually demanded by a score. All manner of aesthetic, technical, and structural decisions must be made, concerning densities, silence, freedom, control, pace, and continuity. Not least of these is the degree to which the look of the score affects the playing: much has been made of the extraordinary graphic character and brilliance of the Solo for Piano but how this translates into sound is rather more elusive. Philip Corner and Mark Knoop were just two of the interviewees who observed that the varied and elaborate graphics are simply means to generate pitches and, in practice, the pitches of one notation may sound very much like those of another, even if the notations look very different from one another. Knoop suggested that he consciously worked to create parallels between notation and sound: ‘Since [Cage has] found different approaches to notate the piece, rather than coming up with a singular, very practical method to realise your performance, I thought it would be more fun just to throw lots of different ideas at it, sometimes at the same time.’ Ian Pace extended this approach to include composition and performance: ‘I’m wanting to write something so that to me the sensation of hearing it would be connected to the sensation of making it. Even though I doubt you’d ever look at that and predict this.’ Similarly, Kubera, talking specifically about density, described wanting ‘to make sure to preserve something of the look of the original score because there’s so many white spaces. I didn’t want the piece to sound crowded.’ Just as some notations—combined with their instructions—might appeal more to some pianists than others, a number of musicians described selecting pages or notations they were drawn to, or ‘had affection for’ (Kubera). For Fabrizio Ottaviucci, the performer's role is highly creative: ‘Cage channels the compositional creativity of the interpreter, forcing it into very conditioning paths, in which, however, it is not possible to pass without a complete creative availability; in the end it is a meeting point between the effort to interpret the rules and its suggestions and the natural artistic sense of the interpreter, which must be free and vital.’

Despite the rules that govern many of the notations, there is still considerable freedom to individualise an interpretation, or allow compositional and aesthetic concerns—and even personal taste—to inform how the music might sound. In part, this might be through the selection of notations—one could choose just notations which involve noises or clusters, or, conversely, just those which involve no noise or only single notes—or it might be through the durations assigned to notations or pages. One interpretation might be reminiscent of Iannis Xenakis or Michael Finnissy, while another might point towards Cecil Taylor, or recall the music of Wandelweiser composer Antoine Beuger. Likewise, the projection of dynamics might, in the absence of instructions to the contrary, be predominantly loud or soft (though Tudor’s widely contrasting dynamics in performance undoubtedly made an impression on Cage and he encouraged a similarly varied approach to his later piano pieces, the Etudes Australes (1974–75)). The possibilities are innumerable, and the performances and recordings that have taken place over the 60 years since the Concert’s composition provide merely the smallest snapshot of how the piece might be conceived.

Echoing de Kooning’s sentiments five years earlier, composer and pianist James Tenney wrote to Cage: ‘As a composer, I find it fascinating, challenging, provoking. As a pianist, it is all these, though somewhat frustrating at the same time’ (13 September, 1963 (Source: John Cage Collection)). There is no doubt that the challenges of the Solo for Piano for any pianist are many and often apparently formidable; however, with a little time—and hopefully with the added benefits of learning from other pianists, including those mentioned here, and through the use of the Solo for Piano app—the rewards are plenty as the 146 notations unravel and combine to generate music which is ever changing and fascinating.

Reading notations

Cage, on a number of occasions, pointed to Tudor’s penchant for solving puzzles, suggesting that his indeterminate notations, especially those of the Solo for Piano, were in some way a gift or challenge to Tudor with which to engage. There is no doubt that much of the fun in preparing the piece is in trying to make sense of the notations and their accompanying instructions, finding solutions of varying degrees of ingenuity.

Rather than explain each of the notations individually here, the Solo for Piano app enables the user to explore each of them by making realisations and trying out possibilities, as well as finding out more about the principles underlying each. What follows here is a brief discussion of some of the more unusual techniques and challenges featured across the score, beyond the myriad of ways in which notes are generated, arranged, and displaced.

Time displacement

Notations are usually read in what is generally referred to as space-time notation, whereby one reads from left to right, aligning the points at which notes occur on the page with when they occur in time, even if the specific total time is indeterminate. Sometimes Cage makes this reading particularly clear, as in notation R, which features equal time divisions above the staff and the instruction ‘[r]igorously in time.’ There are a number of exceptions to this, however.

Notation D specifies that sounds occur ‘sooner’ or ‘later’ than the position that they occupy within the notation, and while ‘sooner’ might imply ‘just before’, as a grace note perhaps, it could also be interpreted as any time before, both within the time span of the notation itself or even earlier, even occurring during an earlier notation. The same might apply mutatis mutandis for ‘later’.

Notation J requires readings in space-time ‘backwards’, the meaning of which is ambiguous, given that time itself may only move forwards. One way of reading this instruction might be to treat it like the ‘sooner’ instruction of D, reading the notes before their placement on the page (though within a more defined time-space, proportional to the left-to-right placing of the notes). But other possibilities might be considered, such as simply reading the material backwards while reading time forwards.

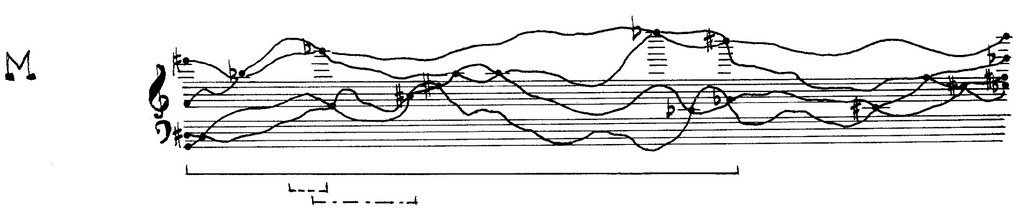

Notations M, Q, and AU allow the pianist to take multiple routes through the notation, including going backwards at each intersection. In M such a move adds time to the notation, while in Q and AU it means an acceleration (or ‘compression’) of events within a fixed duration.

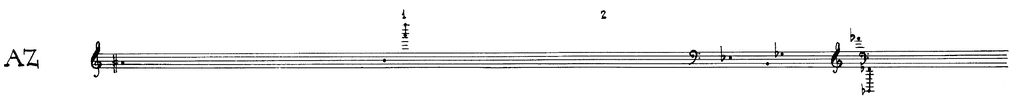

In notations F, Y, AM, AZ and BO, Cage changes the rate at which the notation is read in time, such that what looks like notes to be read in standard space-time fashion are changed by adding numbers or vertical dashes (units of time) in contradiction to the space-time divisions. What appears to be a long duration, then, might be in fact short, and vice versa. Although these create differences between how the notation looks and how it sounds, it is, still, relatively fixed with regard to time, as one realisation will be more or less consistent with another.

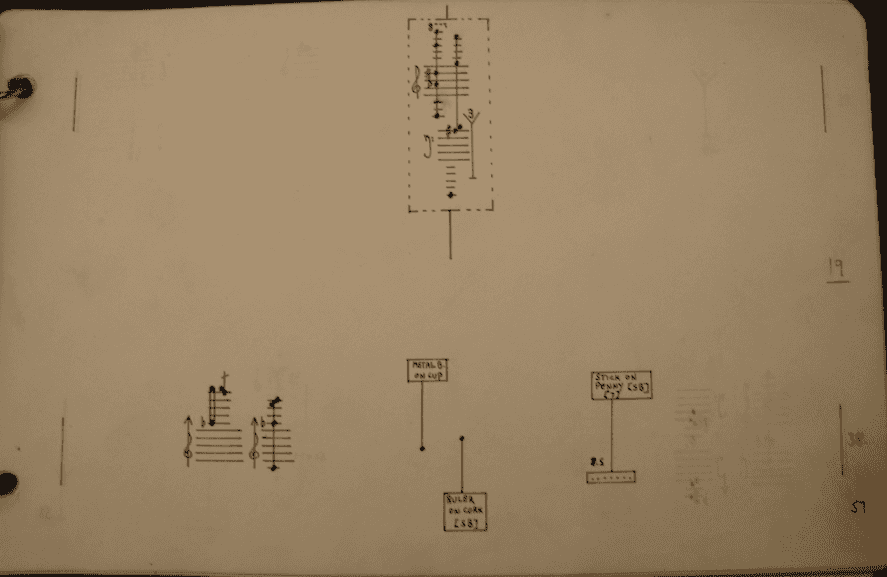

Other notations—such as A, K, BH, BK, and BN—are composed in such a way that a linear, left-to-right reading is to be avoided. In A, BH, and BK, notes are read around the shape in opposite directions, meaning that they will at some point be directed backwards, from right to left (notation AH similarly requires a non-linear approach, following arrows bending round on themselves instead of the usual sequence of notes left to right). In K Cage simply states: ‘Disregard time.’

Note selection

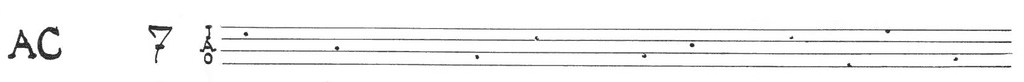

Some notations specify that only a certain number of notes should be played, meaning that a ‘complete’ realisation of the Solo for Piano should only ever be a partial representation of all of the notes on the page. This is the case for notations G, AC, AK, and BE.

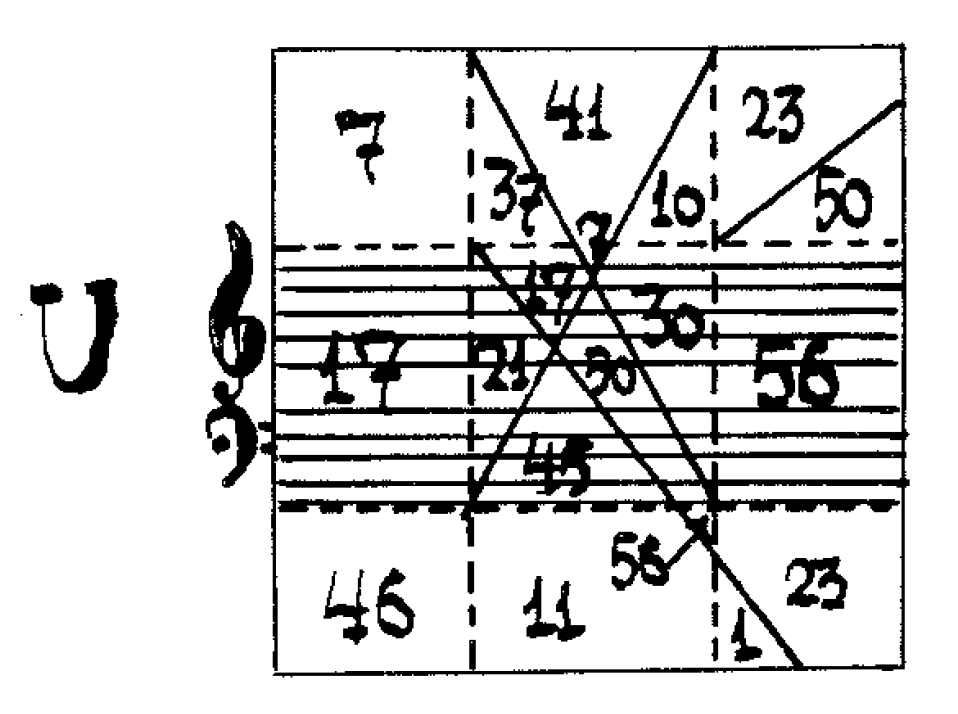

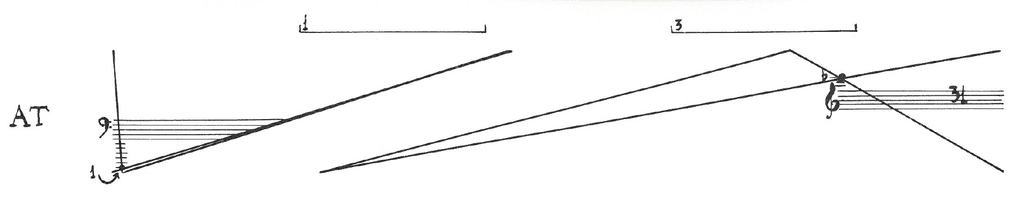

Other notations (J, U, AE, AT, BC, BG, BP, BU, and CB) simply require numbers of sounds to be played within pitch areas. How these notes might be articulated is entirely open and could consist of single notes, dyads, chords, clusters, arpeggios, inside piano techniques, and/or any combination of these and more. However, restrictions must be imposed where the shapes, numbers, and pitch ranges disallow certain possibilities: the 56 notes to be played in the upper right division of the lower middle block of notation U can hardly be played as a cluster of any magnitude, and will certainly involve considerable repetition. Similarly, the 31 notes to be played in the far right area of notation AT (p. 39) are perfectly possible to play but, if adopting a literal left-to-right reading, the possibility of employing clusters becomes greater the further to the right one reads, as the area opens out from the smallest area to the largest.

Durations

For the most part, Cage leaves durations of sounds indeterminate. However, sometimes, as in notations I and X, he notates the ends of sounds, using a slur to the left of the note to indicate when to release/stop the note sounding. In notation AO durations are indicated by horizontal lines.

Pizzicato and Mute

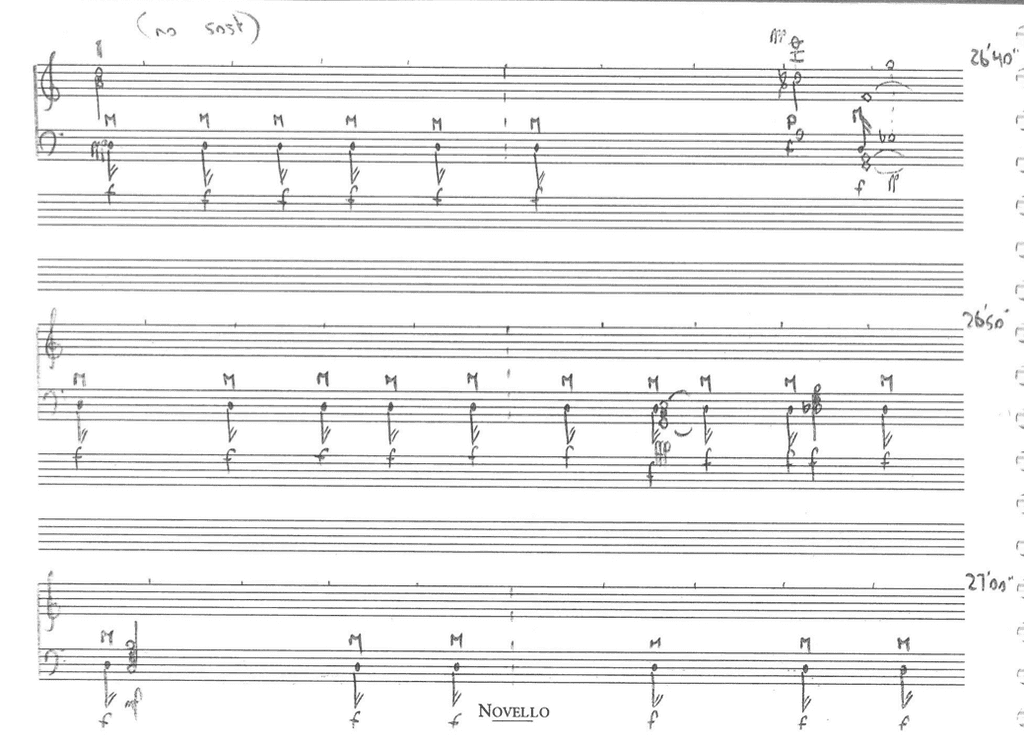

Notations C, H, I, N, S, and CA all require specific notes to be played by either plucking (P) or muting (M) the strings. These are techniques derived from Cage’s earlier set of 84 pieces Music for Piano (1952–56); indeed, notations C and S are almost identical in method to those pieces. To access these notes quickly and easily it is best to mark (carefully) the inside of the piano in some way as each of these notations requires both ‘normal’ playing on the keyboard and inside piano playing, meaning (unless the clock and space-time readings are ignored or treated liberally) some fast manoeuvring between these two positions (though notation I on p. 46 consists of solely plucked notes, so can be executed without the need for moving). Alternatively, notes could be prepared in some manner in advance, an option adopted by pianist John Tilbury for those muted notes of notation C. Plucking and muting the string at different positions along the string, and/or using different parts of the finger or fingernail will create quite different timbres and (in the case of muting) different pitches, and it is worth exploring possibilities for differences in sound.

The instruction for notation G specifies that notes may be played ‘in any manner (key, harp)’, suggesting that the pianist may treat this like the notations described above, playing notes as pizzicati or muted notes, or indeed playing on the strings in any other manner. One might even apply this principle, in the absence of other indications, to other notations.

Harmonics

Cage either directly notates harmonics (with a diamond notehead, as in notations I and N) or specifies in the instructions that they can be used, as in notations B, AI, and BR. By this Cage means to silently depress the note specified (I and N) or selected notes (B, AI, and BR) such that, when other notes are played, harmonics will be sounded (though they may not always be heard particularly loudly). He does not mean that the harmonic should be produced by muting a string at one of its nodes and then played to create a harmonic on that note. One might choose to release the attacked notes earlier to allow the sound of the harmonics to emerge.

‘Graces and punctuations’

Cage uses these terms in different ways: in notation K selected notes are to be played ‘as graces or punctuations’; the grace notes in notations X are ‘punctuations (before, at, during, or end of interval they accompany)’; and in notation AA the grace notes are to be used as ‘assistance’. Without further clarification, how these might be played, and when they might be played in relation to the other notes, is open to interpretation. Some possibilities might be as grace notes before main notes, either immediately before, or some time before, including a long time before (as in the ‘sooner’ described above); as harmonics; as simultaneities with the other note(s), perhaps differentiated in some way (for an excellent point of reference, see Cage’s earlier piano music, such as The Seasons (1947) or Music of Changes (1951), or the music of Morton Feldman); or as notes stemming away from the main note.

Clusters

Piano clusters are a feature of early- to mid-twentieth-century piano music, occurring most famously in the music of composers as diverse as Charles Ives and Henry Cowell to Luciano Berio and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Cage employed piano clusters in some of his earliest piano pieces, in which the influence of Henry Cowell is most apparent, through to the work composed just before the Solo for Piano, namely Winter Music. Tudor was a master of the cluster, and John Holzaepfel (1994) writes that he codified many of his cluster playing techniques in his realisations of the Solo for Piano, demonstrating a great variety of ways of playing clusters, and pianists today would not go far wrong in exploring different cluster techniques themselves: small and large clusters, soft and loud, different articulations, speeds and so on. In notation B clusters are notated as a filled in ‘wedge’ above two notes, indicating that all notes between these two points should be played as a single event. This might require only five fingers if the extremities are close, or both arms if far apart. One might even consider using handmade devices that could extend across the keyboard to depress a wide expanse of notes simultaneously. Notations Z, AB, and AO depict clusters as vertical lines, while notation T calls for ‘a single [cluster] changing in its course’, reflecting the contours of that notation’s shapes, suggesting perhaps the use of cluster glissandi. Other notations do not specify the use of clusters but suggest their employment: notation J for example (p. 26), at one point requires 79 notes to be played within a range of just 51 pitches, which could certainly be played in any number of ways, but two clusters would be both practical and efficient.

Noises

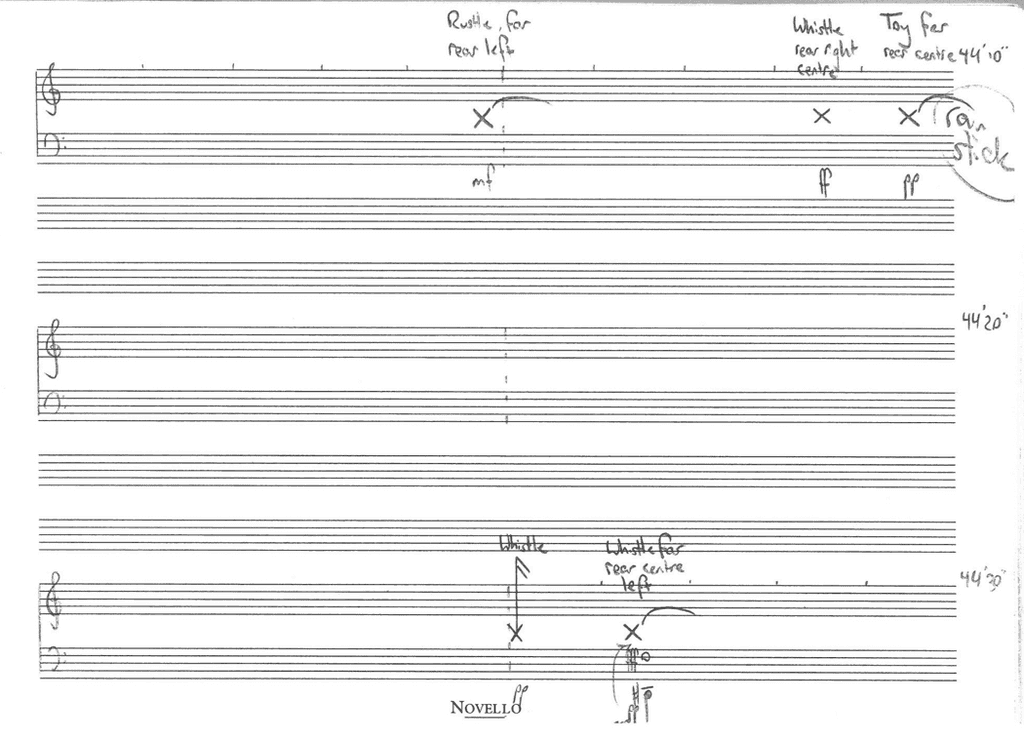

Noises often conform to one of three types: ‘inside piano construction’, ‘outside piano construction’, and ‘auxiliary’. These are used in different ways in notations S, AC, BA, and BK. Inside the piano construction might generally refer to the strings, bars, pegs, frame, and sounding board of the piano, while outside might refer to the sides of the piano, its lower and upper frames, the pedals, the keyboard and upper lid, the lid stand, and the piano legs. However, others might read this division differently and perhaps it’s more important to ensure that the division means something that can be applied throughout the Solo.

Notations P and BY include only noises of any kind—Cage gives free reign to the pianist to explore a range of possibilities, making noises on the piano itself but also using any other object, mechanical, electric, or otherwise. The limitations of the piano for making sounds of duration is countered here by the possibility of employing devices that can sustain sounds for longer than the standard piano attack. By contrast, notation AX suggests a more percussive approach, indicating types of beaters but saying nothing about the objects which are to be struck (or indeed, rubbed or stroked). Notation BT implicitly requires different types of noises as some noteheads are positioned outside of the piano contour or inside the piano (including at the rear of the instrument).

Hands specifications

Notations E, L, AF, and AH instruct the performer as to which hand plays which note (and even where there is indeterminacy as to the pitch, which hand plays it is still specified). While it may at times be tempting to alter the assignations to make it easier to play, if pianists are to fulfil the letter of Cage’s instructions they should avoid doing so: this is a part of the notation, and any resulting time irregularities that result from it are integral to the character of the notation. Of course, in notations E, L, and AH where clefs are ambiguous, the pianist could arrange it so that the most straightforward arrangement of pitches is selected, but even then there will be difficulties, requiring hands crossing over in an at times eccentric and theatrical fashion.

Pedalling

Cage only specifies pedalling in a few notations: notation M includes use of all three pedals—una corda, sustain, and sostenuto—which appear to be randomly applied. Here he marks pedals as being ‘non-obligatory’ and certainly if moving backwards through the notation variously combining different voices the pianist would need to decide how to apply pedalling, or simply ignore the instruction. Notations N and O use pedalling in an entirely conventional manner (although the occasional requirement to depress all three pedals at once requires some careful foot angling), and in notation X the pedalling matches the durations indicated, making possible the various combinations of sounds. Notations BZ and CF are unique in their indications for only pedalling, with no other material present. Each may be interpreted alongside any sounds, or other notations, or alone, as pieces for pedal alone (a selective approach is probably necessary if performed by two feet only).

Dynamics

Dynamics are mostly left indeterminate, but when proscribed they are of three types: a scale of eight dynamics ranging from ppp to fff; a scale of numbers from 1 to 64 (the loudest being either extremity) which might also align with a scale of 8 dynamics (such as, for example, 1–8 = ppp, 9–16 = pp, etc.); or a more indeterminate scale between soft and loud, mapped to the vertical position of the note within a grid.

Measuring and calculating

The Solo for Piano frequently requires the pianist to measure space, whether judging that space by eye or more precisely through measurements using a ruler or similar method. These occur most frequently in the second half of the Solo, although early examples include measuring the position of noteheads within a vertical space to determine dynamics (as in P, Y, and BS), or calculating pitches within a vertical range, as in Y, AO, AQ, and AY, which, while indeterminate, require some consistency of measurements to be applied having made initial decisions as to range. These notations could be read graphically (although Y and AQ also have the complications of time disruptions to work out) or decisions could be made, and then realised, using a ruler (AO, it should be noted, has a height of 20cm, making the division into 20 chromatic tones suggested by (but not limited to) the instructions relatively straightforward.

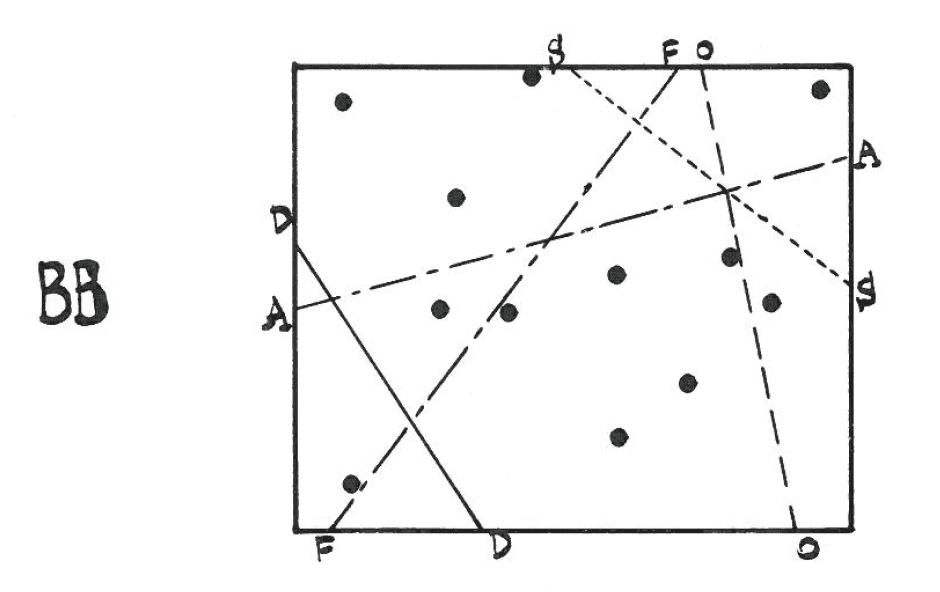

Among the most famous of the notations in the Solo for Piano are BB and those related to it (BJ, BV, and BW), which point forward to the more flexible transparent pages of Cage’s Variations I (1958) and II (1961). The boxes of these notations contain a number of points with straight lines of various kinds. In BB these represent duration, frequency, overtone structure, amplitude, and occurrence. The pianist must, in Cage’s terms, ‘drop’ perpendicular lines from each point to each line, thus determining values for the points, generating as many sound events as there are points. To do so, scales of some kind need to be assigned to each line. For duration one could assign a scale in terms of seconds (0–10 seconds, for example), or length of space (0–10cm, for example); or use words to describe durations (very short to very long, or simply short/long). For frequency an 88-point scale could be devised to represent the piano keys; or a subsection of the piano’s register might be applied, such as a scale of 25 notes, from the lowest A to the A two octaves higher; or a random selection of 10 notes, numbered 1–10, could be applied. Overtone structure is probably the most open and individualised of the values and could be as simple or complex as desired: one option might be to reflect the types of sounds already prevalent in the Solo, such as keyboard, keyboard with pedal, pizzicato, mute, harmonics, noise (perhaps further subdividing the noise category), and numbering these in some kind of order. In a letter to a Miss Epstein dated April 23, 1961, concerning the piece For Paul Taylor and Anita Dencks (1957), which was composed contemporaneously with the Solo for Piano and which would appear, according to Cage’s programme note, to be an ‘application’ of Notation BB, even if presented quite differently, Cage explains ‘Here timbre provides the greatest difficulty, requiring the most imagination. It may be considered as extending from least overtone structure (a sine wave) to most overtone structure (white noise), from simplicity to complexity’ (in Kuhn, 2016, 242–43). For amplitude the easiest option would be a scale of eight values from ppp to fff, as described above. For succession the scale is implicit; points are at different distances from the line, but one could also determine the exact timing of each sound by ascribing a total duration to this line. These are just some of the many options available. Having made these measurements, a sequence of sounds of different durations, amplitudes, frequencies, and overtone structures will be generated and played at different points in time. For the maximum distance, one option could be to assign the point furthest away from the line as maximum, but to avoid there always being a ‘highest’ note, or a ‘loudest’ note, present, one could also take just one maximum value as indicative for all measurements, thus creating the possibility that all sounds might be, for example, soft or high or short. In BV the lines are used multiple times to generate further values for groups of notes. Notation CC (the kernel of Cage’s notations for his later Fontana Mix (1958)) extends these types of measurements, leaving the numbers of sounds unspecified, but, having selected points at which to make sounds, measurements to determine their values.

Open notations

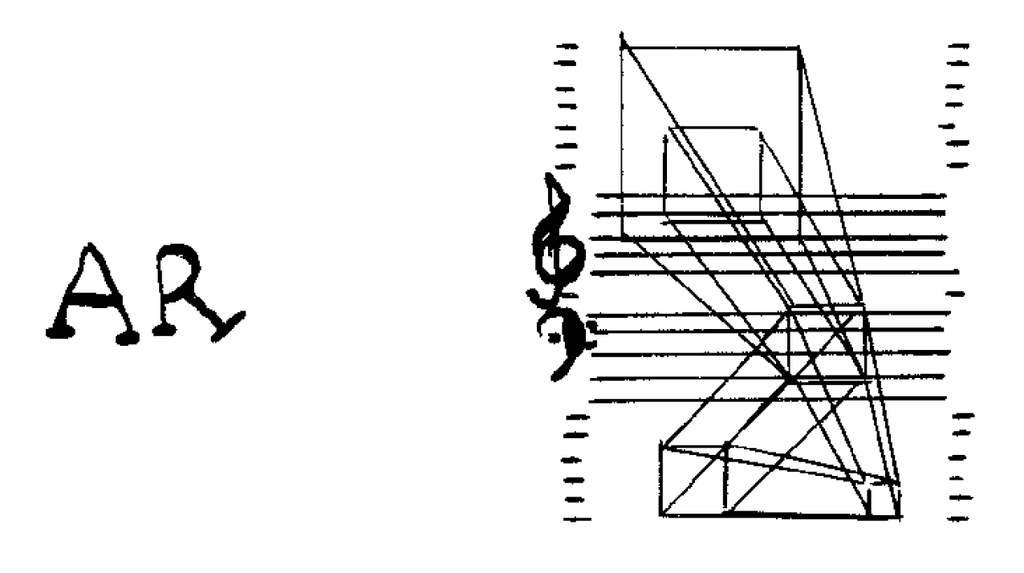

In contrast to those notations which require measurement and precision, others are almost entirely ‘free’. Notations AR and AV have the instruction ‘Play in any way that is suggested by the drawing’, which is so free that one is restricted only be one’s own imagination. However, at the same time, if one considers the drawing within the context of the many other notations within the Solo for Piano which are characterised by musical staves combined with shapes and lines of varying kinds, then one might be more tempted to apply principles of realisation that have some kind of relationship to those other instructions by Cage, perhaps employing measurements, or thinking of the shapes as spaces to be filled in some way.

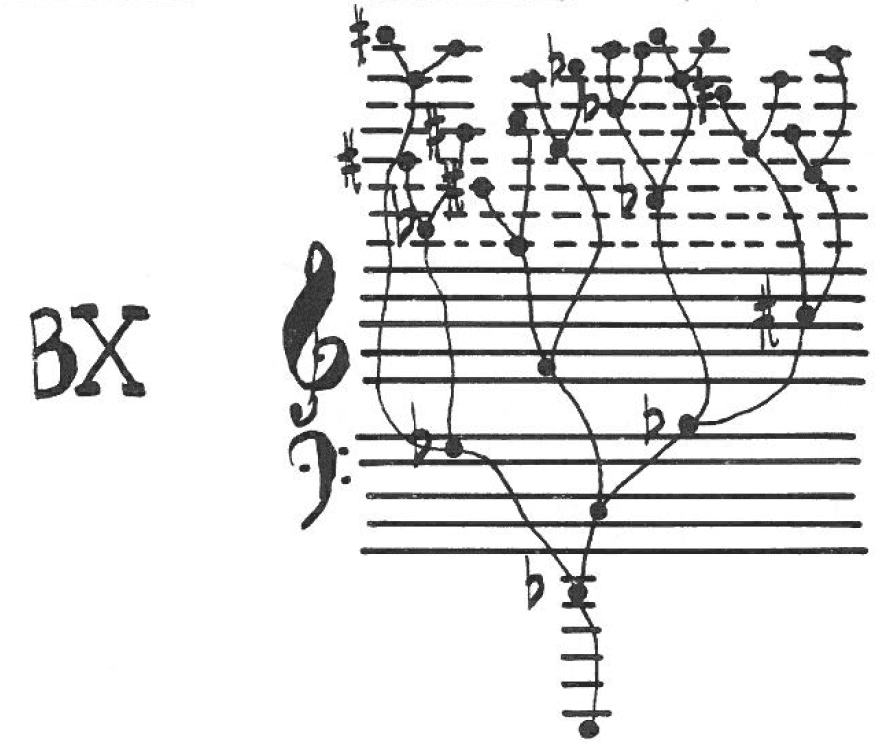

Notation BX—carrying the instruction ‘All at once like a moment of a plant’—is both a description of the notation and a suggestion for its performance. Perhaps, too, it is reflective of the heart of the _Solo for Piano—_at the same time as the (fixed) graphics are impressive and suggestive, they point to something which is not really meant to be thought of as an single object, but rather as a universe from which elements are taken and made usable, requiring decisions to be made which are practical, musical, technical and artistic and which may change from one moment to the next, from one player to another.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Philip Corner, Frank Denyer, Stephen Drury, Mark Knoop, Joseph Kubera, Robert Moran, Fabrizio Ottaviucci, Ian Pace, Marianne Schroeder, John Snijders, and John Tilbury for their sharing their expertise and views on the Solo for Piano with the research team.

Bibliography

John Cage, ‘45′ for a Speaker’, Silence (London: Marion Boyars, 1968 [1954]), 146–93

John Holzaepfel, David Tudor and the Performance of American Experimental Music, 1950–1959 (unpublished doctoral thesis, City University of New York, 1994)

Further reading

John Cage et al., liner notes, The 25-Year Retrospective Concert of the Music of John Cage (Wergo, WER 6247-2, 1994 [1958]) (also in John Cage and Richard Kostelanetz (eds.), John Cage: An Anthology (New York, NY: Da Capo, 1991), 127–131)

John Holzaepfel, ‘David Tudor and the Solo for Piano’, Writings Through John Cage’s Music, Poetry, + Art, eds. David Bernstein and Christopher Hatch (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 137–156

Martin Iddon, John Cage and David Tudor: Correspondence on Interpretation and Performance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013)

Martin Iddon and Philip Thomas, John Cage and the Concert for Piano and Orchestra (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, forthcoming)

Joseph Kubera, ‘Interpreting Cage’s Solo for Piano’, Ostrava Days 2001 Report, eds. Dita Eibenová, Martina Perry, and Jeremy Novak (Ostrava: Ostrava Center for New Music, 2001), 55–60

Petr Kotik, liner notes, John Cage: Concert for Piano and Orchestra/Atlas Eclipticalis (Wergo, WER 6216-2, 1993)

Johanne Rivest, ‘John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra’, Perspectives on American Music since 1950, ed. James R. Heintze (New York, NY: Garland, 1999), 81–94

Discography

Cage a Firenze. Solo for Voice 2 (with simultaneous performance of) Solo for Piano. Giancarlo Cardini, piano; Francesca Della Monica, voice (Materiali Sonori, CAGE 493, 1993)

CC – John Cage: Concert for Piano and Orchestra / Christian Wolff: Resistance. Apartment House; Philip Thomas, piano; Jack Sheen, conductor (Huddersfield Contemporary Records HCR16CD, 2017)

Ensemble Musica Negativa – Music Before Revolution. Concert for Piano and Orchestra performed simultaneously with Solo for Voice 1 and 2. Ensemble Musica Negativa; Hermann Danuser, piano; Bell Imhoff, voice 1; Doris Sandrock, voice 2; Rainer Riehn, conductor (EMI Classics, 50999 2 34454 2 0, 2008 [1972])

John Cage – Complete Piano Music Vol. 4. Steffen Schleiermacher, piano (Musikproduktion Dabringhaus und Grimm, MDG 613 0787-2, 1999)

John Cage – Concert For Piano And Orchestra / Atlas Eclipticalis. Joseph Kubera, piano; The Orchestra of S.E.M. ensemble; Petr Kotik, conductor (Wergo, WER 6216-2, 1992)

John Cage / David Tudor – Indeterminacy: New Aspect of Form in Instrumental and Electronic Music. David Tudor, piano (Folkways FT 3704, 1992 [1959])

John Cage: Dream. Fabrizio Ottaviucci, piano; Mike Svoboda, trombone; Manuel Zurria, flute; Aldo Campagnari, violin; Giorgio Casati, cello; Dario Calderone, double bass; Nextime Ensemble, percussion, Stefano Scodanibbio, conductor (Wergo, WER 6713-2, 2009)

John Cage – Early Piano Works. Steffen Schleiermacher, piano (ITM Media, 950008, 1993)

John Cage: Indeterminacy. Susanne Kessel, piano; Joachim Krol, voice [with Fontana Mix] (Oehms Classics, OC 855, 2012)

John Cage: Solo for Piano. Sabine Liebner, piano (Wergo, WER 6768-2, 2013)

John Cage: The Works for Piano 10. Thomas Schultz, piano (Mode, MOD-CD-304, 2018)

The 25-Year Retrospective Concert of the Music of John Cage. David Tudor, piano; Merce Cunningham, conductor [Live recording of the premiere at the Town Hall, New York City, 1958] (Wergo, WER 6247-2, 1994)

The Barton Workshop Plays John Cage. Barton Workshop; Marianne Schroeder, piano (Etcetera, KTC 3002, 1992)

The works of John Cage are the copyright of Henmar Press Inc., New York and are reproduced by permission of Peters Edition Limited, London. All rights reserved.